|

|

| Plant Pathol J > Volume 38(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Fusarium culmorum is one of the most important causal agents of root rot of wheat. In this study, 10 F. culmorum isolates were collected from farms located in five agro-ecological regions of Morocco. These were used to challenge 20 durum wheat genotypes via artificial inoculation of plant roots under controlled conditions. The isolate virulence was determined by three traits (roots browning index, stem browning index, and severity of root rot). An alpha-lattice design with three replicates was used, and the resulting ANOVA revealed a significant (P < 0.01) effect of isolate (I), genotype (G), and G × I interaction. A total of four response types were observed (R, MR, MS, and S) revealing that different genes in both the pathogen and the host were activated in 53% of interactions. Most genotypes were susceptible to eight or more isolates, while the Moroccan cultivar Marouan was reported resistant to three isolates and moderately resistant to three others. Similarly, the Australian breeding line SSD1479-117 was reported resistant to two isolates and moderately resistant to four others. The ICARDA elites Icaverve, Berghisyr, Berghisyr2, Amina, and Icaverve2 were identified as moderately resistant. Principal component analysis based on the genotypes responses defined two major clusters and two sub-clusters for the 10 F. culmorum isolates. Isolate Fc9 collected in Khemis Zemamra was the most virulent while isolate Fc3 collected in Haj-Kaddour was the least virulent. This work provides initial results for the discovery of differential reactions between the durum lines and isolates and the identification of novel sources of resistance.

Fusarium root rot (FRR) is one of the most important diseases of cereals worldwide whose damages are exacerbated by moisture stress on the plants (Akinsanmi et al., 2004; Burgess et al., 2001; Chakraborty et al., 2006). Hence, the changing climates are favoring the occurrence of these pathogens (Backhouse et al., 2004; Burgess et al., 2001; Smiley et al., 2005).

Despite the importance of FRR, very little is known about either the infection or colonization process of the pathogen or the early host responses (Beccari et al., 2011). The most characteristics symptoms are found at the plant stem base where brown discolorations occur. Then, FRR symptoms becomes more evident as the plant advances towards maturity and are commonly expressed by lodging, discoloration of leaves, interference of water and nutrient translocation, and reductions of grain yield and quality, accompanied by the characteristic whitehead symptom (El Yacoubi et al., 2012; El Yousfi, 2015; Mitter et al., 2006; Strausbaugh et al., 2005). The symptoms of FRR are often associated with those of Fusarium crown rot (FCR) because this disease is also able to infect the crown and stems; the main difference is that FCR does not generally infect the roots (Paulitz, 2006).

Soil-borne Fusarium diseases have been neglected in comparison to the floral disease Fusarium head blight (FHB), which has been the focus of many studies in the past 40 years. Studies on root resistance are generally limited by the difficulty to identify genotype-specific interactions in below-ground pathosystems (Okubara and Paulitz, 2005). Therefore, breeding for FRR resistance is restricted by limited insights into the Fusarium wheat root pathosystem (Kazan et al., 2012; Mudge et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006).

F. culmorum and F. pseudograminearum are the most common and globally important causal agents of FRR and FCR of cereals (Smiley et al., 2005; Wallwork et al., 2004). F. culmorum causes the typical symptoms of wheat head blight, root and crown rot, and mycotoxin contamination of the grain (Chekali et al., 2013; Cook, 2010; Scherm et al., 2013; Tunali et al., 2008; Wagacha and Muthomi, 2007). It is a major constraint to cereal production in many parts of the world, especially in arid and semi-arid regions (Backhouse et al., 2004; Cook 1981; Rossi et al., 1995; Tunali et al., 2008; Van Wyk et al., 1987). Moreover, this pathogen has been shown to be one of the predominant Fusarium spp. in the cooler areas such as north, central and west Europe (Parry et al., 1995) and Canada (Demeke et al., 2005). It has also been identified as one of the predominant Fusarium species in Germany (Muthomi et al., 2000), Turkey (Gebremariam et al., 2018; Tunali et al., 2008), and Japan (Chung et al., 2008). Kosiak et al. (2003) ranked F. culmorum among the four most frequently isolated Fusarium spp. from wheat, barley and oats in Norway. It has also been reported that F. culmorum is one of the most common Fusarium diseases of cereals in Tunisia (Chekali et al., 2013; Oufensou et al., 2019) and the most prevalent agent of FRR in Morocco (El Yacoubi et al., 2012; El Yousfi 1984; Khabouze, 1988).

The biology of F. culmorum causing FRR is different from that of F. pseudograminearum involved in cereal crown rots. F. pseudograminearum is predominantly associated with FCR (Akinsanmi et al., 2004; Chakraborty et al., 2010). It is more frequent in Australia, China, Canada, the Pacific Northwest of the United States, North Africa, South Africa, and the Middle East (Alahmad et al., 2018; Kazan and Gardiner, 2018; Wallwork et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2018). F. pseudograminearum is more frequent in warmer regions; whereas F. culmorum is able to grow at lower temperatures (Doohan et al., 2003). Both pathogens produce lesions on the coleoptile, roots, and subcrown internode and cause browning of the stem bases (Chekali et al., 2013).

The colonization process of F. culmorum in the stem base of wheat seedlings initiates by progression of the fungus through the layers of the leaf sheaths at the stem base. In response to this, the host reaction is thought to include systemic signaling, resulting in the expression of defense-associated genes in leaf sheaths in advance of those infected by the fungus (Beccari et al., 2011). Covarelli et al. (2012) reported that after stem base inoculation, F. culmorum can extensively colonize stem tissues, but it is not able to reach the spikes until plant maturity. However, other studies concluded that none of the Fusarium species can colonize spikes by this route (Burgess et al., 1975; Clement and Parry, 1998; Gelisse et al., 2006; Purss, 1971; Snijders, 1990).

Differences in environmental factors and the relative aggressiveness of the different Fusarium species and strains are probably important reasons for the contrasting results (Diaz Arias, 2012; Wang et al., 2015). It was reported that toxin translocation might occur from the roots (Covarelli et al., 2012; Winter et al., 2013), therefore, further attention on this species should be expected where environmental conditions favor root and crown rot diseases (Scherm et al., 2013).

Wheat is prone to infection with many pathogens causing seed rot and damping-off diseases at different stages of plant growth (Ishtiaq et al., 2019). Under field conditions, Chekali et al. (2013) revealed that bread wheat and durum wheat cultivars seem to be susceptible to FRR but that some bread wheat cultivars had partial resistance. Durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf) damage commonly exceeds 50% reduction in grain yield (Jones and Clifford 1978; Smiley et al., 2005). Many studies have shown that durum wheat is in fact the most sensitive crop to FRR in Morocco (Lyamani, 1988; Mergoum, 1991; Nsarellah et al., 2000). Therefore, the main objective of this study was to find novel sources of resistance to Fusarium culmorum in durum wheat.

A preliminary test involving 89 durum wheat genotypes challenged with FRR mixtures, allowed to identify 20 genotypes showing differential responses. These 20 were used in this study and full information is available in Table 1. This differential set included six Moroccan cultivars, 10 ICARDA’s breeding lines, and four lines with partial resistance against South Australian F. pseudograminearum strains. These lines were all selected from the same cross involving a complex pedigree that included a resistance donor Triticum dicoccon (AUS18743), a South Australian bread wheat × durum hybrid (WID902), three crosses to the durum variety Kalka and two crosses to a South Australian breeding line WI99007.

Infected durum wheat samples, displaying the root rot symptoms, were collected during 2014-2015 and 2017-2018 seasons from five agroecological regions of Morocco. The roots of the samples were sterilized in 3% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min, rinsed thrice with sterile distilled water, and then dried on a sterile paper towel before being mounted on potato dextrose agar medium at 25°C for 3-7 days. The resulting fungal colonies were isolated, purified and identified according to Nelson et al. (1983) and Leslie and Summerell (2006). Single spores of each isolate were grown on SNA plates for 10 days at 25°C. Ten isolates of F. culmorum were chosen for this study, the site of collection are described in Table 2. To harvest the fungus, 10 ml of sterile distilled water were added to the plates, then conidia and mycelium were scraped from the agar surface using a sterile scalpel. The resulting suspension was filtered through two layers of cheesecloth and the conidial concentration for each isolate was adjusted to 106 spores/ml amended with Tween 20.

The seeds of the 20 differential genotypes were surface sterilized in 2% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min followed by 2 min in 70% ethanol, and finally rinsed thrice with sterile distilled water. The seeds were then sown in 10-l pots prepared with an even mixture (1:1:1) of autoclaved soil, peat and sand under controlled greenhouse conditions set at 16 h photoperiod and a temperature of 22±2°C. Each pot contained only one plant. At early stem elongation stage (2nd detectable node, Z32) (Zadoks et al., 1974), plants were carefully removed from the soil mixture to avoid root injury and the root tips were hurt using sterilized scissors. The roots were then dipped into a spore suspension generated from one single isolate for 10 min. For mock test, plants were dipped in sterile distilled water. The inoculation tray hosted five genotypes to ensure only root tips came into contact with the solution. Three plants per genotype per isolate were treated, for a total of 20 genotypes, three replicates, 10 isolates and one mock treatment. The experiment designed was an alphalattice design with three replicates, and four sub-blocks of size five, corresponding to the five genotypes that fit together inside one inoculation tray, and 20 being the number of pots that fit on one glasshouse bench.

At maturity (Z75), each plant was carefully pulled from the pots and rinsed under running water. The stem discoloration (stem browning index [SBI]) was evaluated as described by Wallwork et al. (2004). The roots were rated for the extent of discoloration (root browning index, RBI) using a 0-4 scale: 0, no visible symptoms; 1, slightly necrotic; 2, moderately necrotic; 3, severely necrotic; 4, completely necrotic. Both indexes for stem and roots were combined into a root rot severity (RRS) value assessed on a scale of 0-5: 0, no discoloration; 1, small scattered necrotic lesions on subcrown internode or roots; 2, distinct dark lesions of basal parts particularly on subcrown internode and roots; 3, large necrotic lesions on crown, subcrown internode and roots with loss of plant vigor; 4, severe rotting of basal parts, plant chlorotic often wilted or stunted, some culms dead; 5, plant was killed before reaching maturity.

The three measured traits were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using META-R software (Alvarado et al., 2015) assuming genotypes and isolates as fixed effects. The basic linear unbiased estimates (BLUEs) value was calculated for each genotype and each isolate, and the least significant difference (LSD) value was also derived for each isolate (P < 0.01). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed by GEA-R software (Pacheco et al., 2015) using the BLUEs of RRS as inputs to define the existing similarities between isolates. Based on the LSD calculated for each isolate, the response of the genotype to RRS was divided into four classes corresponding to once, twice, three times, and more LSD value. To each class was assigned a resistant (R), moderately resistant (MR), moderately susceptible (MS), and susceptible (S) disease response value, respectively.

The ANOVA for the three traits (SBI, RBI, and RRS) revealed significant differences among genotypes, isolates, and genotypes by isolates (P < 0.01) (Table 3). The interaction explained most of the phenotypic variation for RBI and RRS at 48% and 53%, respectively. For SBI the isolate effect was instead superior to all other sources of variations with 56%. For all three traits, the effect of isolates was superior to what explained by genotypes, suggesting that a portion of the pathogenicity could not be captured by this set of differential genotypes. The coefficient of variation of all experiments was below 22%, and the heritability reached 73%, 64%, and 74% for RBI, SBI, and RRS, respectively.

A total set of 20 durum wheat genotypes were challenged with 10 F. culmorum isolates (Table 4). In all cases the genotypes presented differential responses to the isolates. Only the major Moroccan commercial cultivar ‘Karim’ was susceptible to all isolates. Five genotypes showed MR response to at least one isolate, and other five were recorded as MR against two or three isolates. The recently released Moroccan cultivar ‘Faraj’ resulted susceptible (MS or S) against six isolates, but MR against four. Seven genotypes resulted as providing R response to at least one isolate, among these was the Moroccan cultivar ‘Marouane’, with six resistance (R or MR) responses, and the Australian resistance source SSD1479-117, also with resistance (R or MR) responses. It is worth mentioning also the ICARDA’s elite lines ‘Icaverve’ and ‘Berghisyr’ as these combined R responses with MR against isolate INRA-Fc10. No genotype showed resistance against all isolates. From a breeding standpoint, the pyramiding of Marouane, SSD1479-117, Berghisyr2, and Faraj could provide resistances (MR or R) against nine isolates, and MS response to the highly virulent isolate INRA-Fc9.

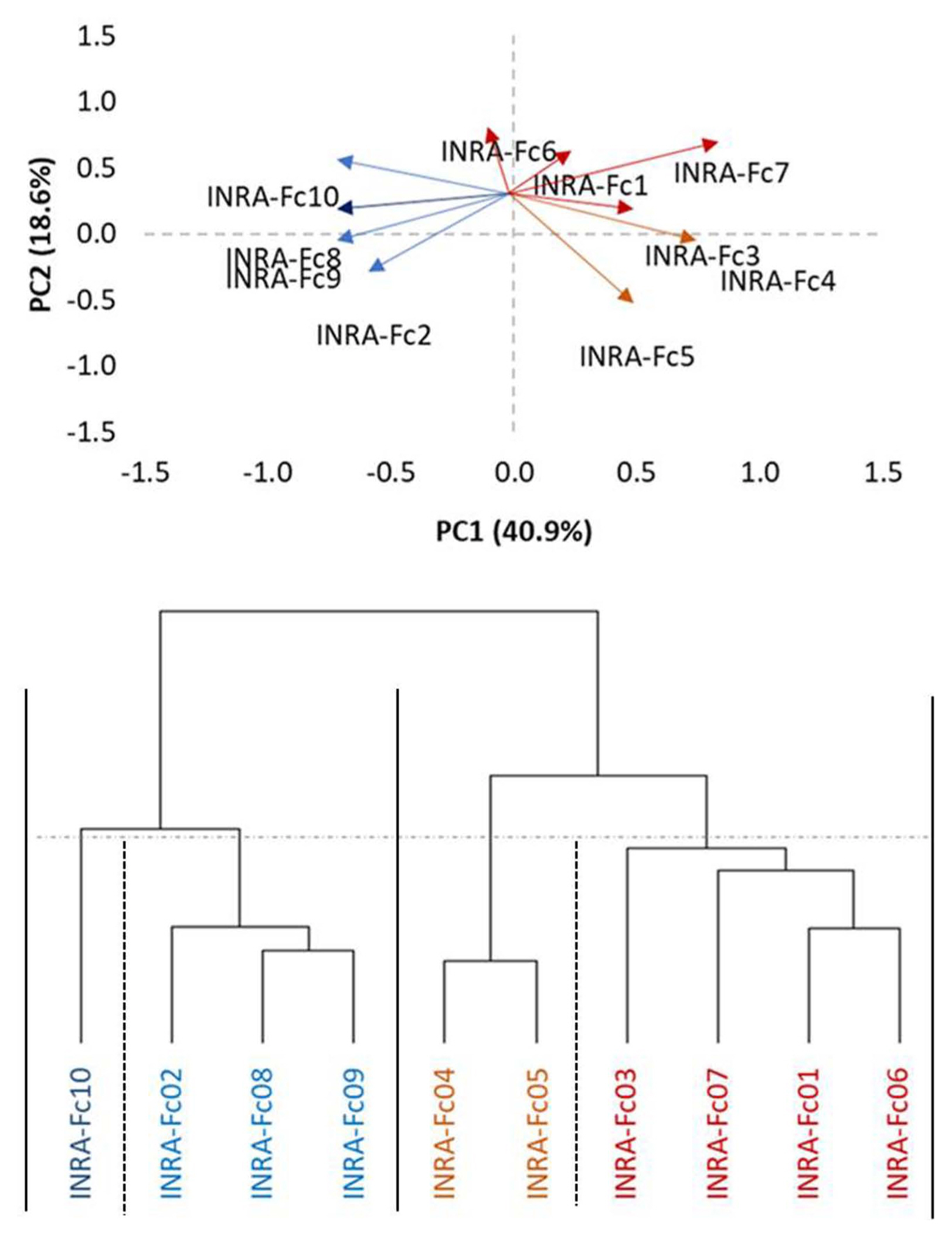

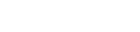

All isolates of F. culmorum significantly increased disease incidence compared to mock inoculated plants. In order of virulence, the isolate INRA-Fc3, INRA-Fc1, INRA-Fc2, INRA-Fc6, INRA-Fc7, INRA-Fc4, INRA-Fc10, INRA-Fc5, INRA-Fc8, and INRA-Fc9 resulted between eight to all genotypes being recorded as susceptible (MS or S). In particular, INRA-Fc9 was virulent on all genotypes, while for INRA-Fc8 only MR reactions were recorded for the three Moroccan cultivars ‘Faraj’, ‘Marjana’, and ‘Toumouh’. This wide range of phenotypic responses shown by the 20 genotypes against the 10 isolates, and the significant interaction between genotypes and isolates prompts to a more in-depth study of the virulence spectrum among isolates. PCA test among the 10 isolates according to their RRS disease response on the genotypes defined two main clades and two sub-clades (Fig. 1). Clade I consisted of the isolates INRA-Fc2, INRA-Fc8, INRA-Fc9, and INRA-Fc10 originated from Merchouch, Jemaa Shaim, Khemis Zemamra, and Annoceur, respectively. This cluster groups three of the four most virulent isolates with a mild one (IN-RA-Fc2), and no evident geographical distribution (Fig. 2). Clade II grouped the remaining isolates INRA-Fc1, INRA-Fc3, INRA-Fc4, INRA-Fc5, INRA-Fc6, and INRA-Fc7 collected throughout Morocco, of which only INRA-Fc5 was identified as highly virulent. The cartographic distribution of isolates belonging to different clades is presented in Fig. 2, but no obvious geographical dispersion pattern can be observed.

The study of resistance to fungi attacking the roots is hindered by the difficulty of identifying genotype-specific interactions in below-ground pathosystems and finding a genotype with an acceptable level of resistance (Okubara and Paulitz, 2005). FRR resistance is no exception, making breeding for resistance a daunting challenge due to the limited insights into the Fusarium wheat root pathosystem (Kazan et al., 2012; Mudge et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006). Similarly to FHB, wheat resistance against FCR and FRR is partial and often quantitative in nature (Beccari et al., 2011; Bovill et al., 2006; Collard et al., 2005; Wallwork et al., 2004).

Despite the efforts made by pathologists to find resistance to FCR, only a few quantitative trait loci have been detected (Bovill et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010a; Ma et al., 2010; Poole et al., 2012; Wallwork et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2014). Wallwork et al. (2004) have reported that the lines ‘2-49’ and ‘Sunco’ were equally resistant to F. culmorum and F. pseudogramineaum. FRR caused by F. culmorum is less studied and limited reports of resistance exist.

The first wheat genotypes showing partial resistance against seedling root rot have been described only very recently (Wang et al., 2015) with the cultivar ‘Florence-Aurore’ and breeding Line 162.11 that showed characteristics of partial resistance to root colonization by F. graminearum. Alternatively, Li et al. (2010b) suggested that the observed partial resistance against seedling root rot is likely dependent on the plant age. Previous reports have demonstrated that Fusarium spp. release several virulence factors after penetration that can rapidly overcome simple defence mechanisms (Kang and Buchenauer, 1999, 2000; Phalip et al., 2005; Proctor et al., 1995; Voigt et al., 2005). Vergne et al. (2010) have defined that partial resistance is first characterized by a quantitative limitation to the pathogen growth, and Beccari et al. (2011) have suggested that the inability of the pathogen to enter the vascular tissue is a major mechanism of FRR resistance. Thus, partial FRR resistance is characterized by three aspects: (1) no evident resistance during seedling against epidermis penetration and invasion, but (2) resistance to the infection of cortical root cells, which is assumed to result in a delayed and reduced migration into the stem base, and (3) a resistance to vascular bundle infection in stem tissues (Wang et al., 2015). For seedling root rot disease, a few major wheat resistance sources are reported (Li and Yin, 2008; Mitter et al., 2006; Wildermuth et al., 2001).

In the present work, 10 isolates of F. culmorum, the main causal agent of FRR in Morocco were used to challenge 20 durum wheat genotypes. The three traits tested resulted in high heritabilities, suggesting a strong genetic control. Significant statistical differences could be observed among genotypes, isolates, and their interactions. Despite being a relatively small dataset, an array of different responses could be observed (Table 3). Fifty-three percent of the total phenotypic variation could be explained by interactions between host and pathogen genes. These findings are in agreement with several authors who suggested that resistance to root rot diseases can only be obtained by pyramiding several resistance genes. Nevertheless, moderately resistant genotypes could already be found, with adequate response to half of the tested isolates such as the Moroccan cultivar ‘Marouane’ and the Australian breeding line ‘SSD1479-117’. The pyramiding of the resistance loci of ‘Marouane’, ‘SSD1479-117’, ‘Berghisyr2’, and ‘Faraj’ would be sufficient to develop new varieties with good resistance against most of the tested isolates. However, no resistance could be identified against INRA-Fc9. A special mention should be made for the SSD set developed by South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). These entries have been developed over several generations of crosses and selecting for resistance against F. pseudograminearum utilising an outdoor terrace system where crown rot is screened on adult plants (Wallwork et al., 2004). Testing against F. culmorum isolates, one entry confirmed its resistance against six of the 10 isolates.

The set of 20 lines presented here appears as an ideal initial panel to develop differentials to distinguish F. culmorum virulence patterns. This first screening failed to identify any two isolates with identical virulence/avirulence response. Mitter et al. (2006) also reported that field populations of F. culmorum isolates had high genetic diversity, even among isolates obtained from a single farm. Furthermore, Tunali et al. (2008) showed that the incidence of Fusarium spp. varies among 11 agro-ecological zones in Turkey. PCA was used to attempt a high-level grouping of the isolates. It defined two major clades and two subclades, but these did not appear as matching any evident geographical distribution. This result was remarkably similar to what was observed by Gamba et al. (2017) when attempting to map the race structure of Pyrenophora triticirepentis across Morocco. Apparently, the unique socioagro-ecology of this country favors the specialization of different pathotypes in different areas.

In conclusion, FRR caused by F. culmorum is a widespread disease in the drylands of the Mediterranean basin and it has major negative effects on durum wheat productivity. Here, we report a first attempt at better characterizing the spectrum of virulence of this fungus and the differential interactions between the durum lines and isolates. Furthermore, we report several interesting sources of resistance that can be exploited by breeders, even though we remain ignorant of the actual mechanism governing it. An international effort to incorporate these additional resistance sources and use them to characterize more isolates should help obtain the answers needed to fight this challenging pathogen.

Fig. 1

A hierarchical cluster dendrogram showing similarity of 10 Fusarium culmorum isolates based on phenotypic data of 20 Durum wheat genotypes after seedling inoculation using the ward method. Isolates are clustered in a total of four sub-clades including two major clades and two sub-clades.

Table 1

List of durum wheat genotypes used in this study

Table 2

Basic information of the isolates of Fusarium culmorum used in this study

Table 3

Roots browning index, stem browning assessment, and severity of root rot of wheat seedlings inoculated with Fusarium culmorum

| Source of variation | Ratio of total variation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Roots browning index | Stem browning index | Severity of root rot | |

| Isolate (%) | 21** | 56** | 11** |

| Genotype (%) | 15** | 6** | 17** |

| Genotype × Isolate (%) | 48** | 27** | 53** |

| Error (%) | 17 | 11 | 19 |

| LSD | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.22 |

| CV | 19.64 | 19.42 | 21.28 |

| Heritability (%) | 73 | 64 | 74 |

Table 4

Fusarium root rot severity response of 20 durum wheat genotypes inoculated with 10 Fusarium culmorum isolates

References

Akinsanmi, O. A., Mitter, V., Simpfendorfer, S., Backhouse, D. and Chakraborty, S. 2004. Identity and pathogenicity of Fusarium spp. isolated from wheat fields in Queensland and northern New South Wales. Aust J. Agric. Res. 55:97-107.

Alahmad, S., Dinglasan, E., Leung, K. M., Riaz, A., Derbal, N., Voss-Fels, K. P., Able, J. A., Bassi, F. M., Christopher, J. and Hickey, L. T. 2018. Speed breeding for multiple quantitative traits in durum wheat. Plant Methods 14:36.

Alvarado, G., López, M., Vargas, M., Pacheco, A., Rodríguez, F., Burgueño, J. and Crossa, J. 2015. META-R (Multi environment trial analysis with R for windows) Version 6.04. CIMMYT Research Data & Software Repository Network, Texcoco, Mexico.

Backhouse, D., Abubakar, A. A., Burgess, L. W., Dennis, J. I., Hollaway, G. J., Wildermuth, G. B., Wallwork, H. and Henry, F. J. 2004. Survey of Fusarium species associated with crown rot of wheat and barley in eastern Australia. Australas. Plant Pathol. 33:255-261.

Beccari, G., Covarelli, L. and Nicholson, P. 2011. Infection processes and soft wheat response to root rot and crown rot caused by Fusarium culmorum. Plant Pathol. 60:671-684.

Bovill, W. D., Horne, M., Herde, D., Davis, M., Wildermuth, G. B. and Sutherland, M. W. 2010. Pyramiding QTL increases seedling resistance to crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum) of wheat (Triticum aestivum). Theor. Appl. Genet. 121:127-136.

Bovill, W. D., Ma, W., Ritter, K., Collard, B. C. Y., Davis, M., Wildermuth, G. B. and Sutherland, M. W. 2006. Identification of novel QTL for resistance to crown rot in the doubled haploid wheat population ‘W21MMT70’ × ‘Mendos’. Plant Breed 125:538-543.

Burgess, L. W., Backhouse, D., Summerell, B. A. and Swan, L. J. 2001. Crown rot of wheat. In: Fusarium-Paul E Nelson Memorial Symposium, eds. by B. A. Summerell, J. F. Leslie, D. Backhouse, W. L. Bryden and L. W. Burgess, pp. 271-294. The American Phytopathological Society Press, St. Paul, MN, USA.

Burgess, L. W., Wearing, A. H. and Toussoun, T. A. 1975. Surveys of Fusaria associated with crown rot of wheat in eastern Australia. Aust J. Agric. Res. 26:791-799.

Chakraborty, S., Liu, C. J., Mitter, V., Scott, J. B., Akinsanmi, O. A., Ali, S., Dill-Macky, R., Nicol, J., Backhouse, D. and Simpfendorfer, S. 2006. Pathogen population structure and epidemiology are keys to wheat crown rot and Fusarium head blight management. Australas. Plant Pathol. 35:643-655.

Chakraborty, S., Obanor, F., Westecott, R. and Abeywickrama, K. 2010. Wheat crown rot pathogens Fusarium graminearum and F. pseudograminearum lack specialization. Phytopathology 100:1057-1065.

Chekali, S., Gargouri, S., Berraies, S., Gharbi, M. S., Nicol, M. J. and Nasraoui, B. 2013. Impact of Fusarium foot and root rot on yield of cereals in Tunisia. Tunis J. Plant Prot. 8:75-86.

Chung, W.-H., Ishii, H., Nishimura, K., Ohshima, M., Iwama, T. and Yoshimatsu, H. 2008. Genetic analysis and PCR-based identification of major Fusarium species causing head blight on wheat in Japan. J. Gen Plant Pathol. 74:364-374.

Clement, J. A. and Parry, D. W. 1998. Stem-base disease and fungal colonisation of winter wheat grown in compost inoculate with Fusarium culmorum, F. graminearum and Microdochium nivale. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104:323-330.

Collard, B. C. Y., Grams, R. A., Bovill, W. D., Percy, C. D., Jolley, R., Lehmensiek, A., Wildermuth, G. and Sutherland, M. W. 2005. Development of molecular markers for crown rot resistance in wheat: mapping of QTL for seedling resistance in a ‘2-49’ x ‘Janz’ population. Plant Breed 124:532-537.

Cook, R. J. 1981. Fusarium diseases of wheat and other small grains in North America. In: Fusarium: diseases, biology and taxonomy, eds. by P. E. Nelson, T. A. Toussoun and R. J. Cook, pp. 39-52. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, USA.

Cook, R. J. 2010. Fusarium root, crown, and foot rots and associated seedling diseases. In: Compendium of wheat diseases and pests, 3rd ed. eds. by W. W. Bockus, R. L. Bowden, R. M. Hunger, WL. Morrill, T. D. Murray and R. W. Smiley, pp. 37-39. The American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN, USA.

Covarelli, L., Beccari, G., Steed, A. and Nicholson, P. 2012. Colonization of soft wheat following infection of the stem base by Fusarium culmorum and translocation of deoxynivalenol to the head. Plant Pathol. 61:1121-1129.

Demeke, T., Clear, R. M., Patrick, S. K. and Gaba, D. 2005. Species-specific PCR-based assays for the detection of Fusarium species and a comparison with the whole seed agar plate method and trichothecene analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 103:271-284.

Doohan, F. M., Brennan, J. and Cooke, B. M. 2003. Influence of climatic factors on Fusarium species pathogenic to cereals. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 109:755-768.

Diaz Arias, M. M. 2012. Fusarium species infecting soybean roots: frequency, aggressiveness, yield impact and interaction with the soybean cyst nematode. PhD thesis. Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA.

El Yacoubi, H., Hassikou, R., Badoc, A., Rochdi, A. and Douira, A. 2012. Complexe fongique de la pourriture racinaire du blé tendre au nord-ouest du maroc [Root rot fungal complex of soft wheat in northwestern Morocco]. Bull Soc Pharm Bordeaux 151:35-48 (in French).

El Yousfi, B. 1984. Contribution à l’étude de l’étiologie, de l’épidémiologie et des pertes de rendements dues aux pourritures racinaires du blé et de l’orge. Contribution to the study of the etiology, epidemiology and yield losses due to root rots in wheat and barley. Mémoire du 3ème cycle Agronomique, Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II, Rabat, Morocco. pp. 175.(in French).

El Yousfi, B. 2015. Guide du diagnostic des principales maladies des céréales d’automne au Maroc. Guide to the diagnosis of the main diseases of autumn cereals in Morocco. INRA CRRA de Settat, Settat, Morocco. pp. 13.(in French).

Gamba, F. M., Bassi, F. M. and Finckh, M. R. 2017. Race structure of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis in Morocco. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 56:119-126.

Gebremariam, E. S., Sharma-Poudyal, D., Paulitz, T. C., Erginbas-Orakci, G., Karakaya, A. and Dababat, A. A. 2018. Identity and pathogenicity of Fusarium species associated with crown rot on wheat (Triticum spp.) in Turkey. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 150:387-399.

Gelisse, S., Pelzer, E., Doré, T. and Lannou, C. 2006. Contamination des épis et des grains par la fusariose du blé : test de la voie systémique et risque lié aux contaminations tardives [Contamination of ears and grains by Fusarium wilt of wheat: test of the systemic route and risk associated with late contamination]. Phytoma la Défense des Végétaux 596:28-32 (in French).

Ishtiaq, M., Hussain, T., Bhatti, K. H., Adesemoye, T., Maqbool, M., Azam, S. and Ghani, A. 2019. Management of root rot diseases of eight wheat varieties using resistance and biological control agents techniques. Pak J. Bot. 51:327-339.

Jones, D. G. and Clifford, B. C. 1978. Cereal diseases: their pathology and control. BASF, Ipswich, UK. pp. 279.

Kang, Z. and Buchenauer, H. 1999. Immunocytochemical localization of fusarium toxins in infected wheat spikes by Fusarium culmorum. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 55:275-288.

Kang, Z. and Buchenauer, H. 2000. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical investigation of pathogen development and host responses in resistant and susceptible wheat spikes infected by Fusarium culmorum. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 57:255-268.

Kazan, K. and Gardiner, D. M. 2018. Fusarium crown rot caused by Fusarium pseudograminearum in cereal crops: recent progress and future prospects. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19:1547-1562.

Kazan, K., Gardiner, D. M. and Manners, J. M. 2012. On the trail of a cereal killer: recent advances in Fusarium graminearum pathogenomics and host resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13:399-413.

Khabouze, M. 1988. Contribution à l’étude des pourritures racinaires du blé [Contribution to the study of root rots in wheat]. Mémoire du 3ème cycle. Institut Agronomique et Vétérinaire Hassan II, Rabat, Morocco. pp. 113.(in French).

Kosiak, B., Torp, M., Skjerve, E. and Thrane, U. 2003. The prevalence and distribution of Fusarium species in Norwegian cereals: a survey. Acta Agric. Scand 53:168-176.

Leslie, J. F. and Summerell, B. A. 2006. The Fusarium laboratory manual. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, USA. pp. 400.

Li, G. and Yin, Y. 2008. Jasmonate and ethylene signaling pathway may mediate Fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Crop Sci. 48:1888-1896.

Li, H. B., Xie, G. Q., Ma, J., Liu, G. R., Wen, S. M., Ban, T., Chakraborty, S. and Liu, C. J. 2010a. Genetic relationships between resistances to Fusarium head blight and crown rot in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 121:941-950.

Li, X., Zhang, J. B., Song, B., Li, H. P., Xu, H. Q., Qu, B., Dang, F. J. and Liao, Y. C. 2010b. Resistance to Fusarium head blight and seedling blight in wheat is associated with activation of a cytochrome P450 gene. Phytopathology 100:183-191.

Lyamani, A. 1988. Wheat root rot in west central Morocco and effects of Fusarium culmorum and Helminthosporium sativum seed and soil-born inoculum on root rot development, plant emergence and crop yield. PhD thesis. Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA.

Ma, L. J., van der Does, H. C., Borkovich, K. A., Coleman, J. J., Daboussi, M. J., Di Pietro, A., Dufresne, M., Freitag, M., Grabherr, M., Henrissat, B., Houterman, P. M., Kang, S., Shim, W. B., Woloshuk, C., Xie, X., Xu, J. R., Antoniw, J., Baker, S. E., Bluhm, B. H., Breakspear, A., Brown, D. W., Butchko, R. A., Chapman, S., Coulson, R., Coutinho, P. M., Danchin, E. G., Diener, A., Gale, L. R., Gardiner, D. M., Goff, S., Hammond-Kosack, K. E., Hilburn, K., Hua-Van, A., Jonkers, W., Kazan, K., Kodira, C. D., Koehrsen, M., Kumar, L., Lee, Y. H., Li, L., Manners, J. M., Miranda-Saavedra, D., Mukherjee, M., Park, G., Park, J., Park, S. Y., Proctor, R. H., Regev, A., Ruiz-Roldan, M. C., Sain, D., Sakthikumar, S., Sykes, S., Schwartz, D. C., Turgeon, B. G., Wapinski, I., Yoder, O., Young, S., Zeng, Q., Zhou, S., Galagan, J., Cuomo, C. A., Kistler, H. C. and Rep, M. 2010. Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature 464:367-373.

Mergoum, M. 1991. Effects of infection by Fusarium acuminatum, Fusarium culmorum or Cochliobolus sativus on wheat. PhD thesis. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA.

Mitter, V., Zhang, M. C., Liu, C. J., Ghosh, R., Ghosh, M. and Chakraborty, S. 2006. A high-throughput glasshouse bioassay to detect crown rot resistance in wheat germplasm. Plant Pathol. 55:433-441.

Mudge, A. M., Dill-Macky, R., Dong, Y., Gardiner, D. M., White, R. G. and Manners, J. M. 2006. A role for the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol in stem colonisation during crown rot disease of wheat caused by Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium pseudograminearum. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 69:73-85.

Muthomi, J. W., Schütze, A., Dehne, H. W., Mutitu, E. W. and Oerke, E.-C. 2000. Characterization of Fusarium culmorum isolates by mycotoxin production and aggressiveness to winter wheat. J. Plant Dis Prot. 107:113-123.

Nelson, P. E., Toussoun, T. A. and Marasas, W. F. O. 1983. Fusarium species: an illustrated manual for identification. The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA, USA. pp. 206.

Nsarellah, N., Lhaloui, S. and Nachit, M. 2000. Breeding durum wheat for biotic stresses in the Mediterranean region. In: Durum wheat improvement in the Mediterranean region: new challenges, eds. by C. Royo, M. Nachit, N. Di Fonzo and J. L. Araus, pp. 341-347. CIHEAM, Zaragoza, Spain.

Oufensou, S., Balmas, V., Scherm, B., Rau, D., Camiolo, S., Prota, V. A., Ben-Attia, M., Gargouri, S., Pasquali, M., ElBok, S. and Migheli, Q. 2019. Genetic variability, chemotype distribution, and aggressiveness of Fusarium culmorum on durum wheat in Tunisia. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 58:103-113.

Okubara, P. A. and Paulitz, T. C. 2005. Root defense responses to fungal pathogens: a molecular perspective. Plant Soil 274:215-226.

Pacheco, A., Vargas, M., Alvarado, G., Rodríguez, F., Crossa, J. and Burgueño, J. 2015. GEA-R (Genotype x Environment analysis with R for windows) version 4.1. CIMMYT Research Data & Software Repository Network, Texcoco, Mexico.

Parry, D. W., Jenkinson, P. and McLeod, L. 1995. Fusarium ear blight (scab) in small grain cereals: a review. Plant Pathol. 44:207-238.

Paulitz, T. C. 2006. Low input no-till cereal production in the Pacific Northwest of the U.S.: the challenges of root diseases. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 115:271-281.

Phalip, V., Delalande, F., Carapito, C., Goubet, F., Hatsch, D., Leize-Wagner, E., Dupree, P., Dorsselaer, A. V. and Jeltsch, J. M. 2005. Diversity of the exoproteome of Fusarium graminearum grown on plant cell wall. Curr. Genet. 48:366-379.

Poole, G. J., Smiley, R. W., Paulitz, T. C., Walker, C. A., Carter, A. H., See, D. R. and Garland-Campbell, K. 2012. Identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for resistance to Fusarium crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum) in multiple assay environments in the Pacific Northwestern US. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125:91-107.

Proctor, R. H., Hohn, T. M. and McCormick, S. P. 1995. Reduced virulence of Gibberella zeae caused by disruption of a trichothecene toxin biosynthetic gene. Mol. Plant.-Microbe. Interact. 8:593-601.

Purss, G. S. 1971. Pathogenic specialization in Fusarium graminearum. Aust J. Agric. Res. 22:553-561.

Rossi, V., Cervi, C., Chiusa, G. and Languasco, L. 1995. Fungi associated with foot rots on winter wheat in Northwest Italy. J. PhytoPathol. 143:115-119.

Scherm, B., Balmas, V., Spanu, F., Pani, G., Delogu, G., Pasquali, M. and Migheli, Q. 2013. Fusarium culmorum: causal agent of foot and root rot and head blight on wheat. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14:323-341.

Smiley, R. W., Gourlie, J. A., Easley, S. A., Patterson, L. M. and Whittaker, R. G. 2005. Crop damage estimates for crown rot of wheat and barley in the Pacific Northwest. Plant Dis. 89:595-604.

Snijders, CHA. 1990. Systemic fungal growth of Fusarium culmorum in stems of winter wheat. J. PhytoPathol. 129:133-140.

Strausbaugh, C. A., Overturf, K. and Koehn, A. C. 2005. Pathogenicity and real-time PCR detection of Fusarium spp. in wheat and barley roots. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 27:430-438.

Tunali, B., Nicol, J. M., Hodson, D., Uçkun, Z., Büyük, O., Erdurmuş, D., Hekimhan, H., Aktaş, H., Akbudak, M. A. and Bağci, S. A. 2008. Root and crown rot fungi associated with spring, facultative, and winter wheat in Turkey. Plant Dis. 92:1299-1306.

Van Wyk, P. S., Los, O., Rheeder, J. P. and Marasas, W. F. O. 1987. Fusarium species associated with crown rot of wheat in the Humansdorp District, Cape Province. Phytophylactica 19:343-344.

Vergne, P., Maene, M., Gabant, G., Chauvet, A., Debener, T. and Bendahmane, M. 2010. Somatic embryogenesis and transformation of the diploid Rosa chinensis cv Old Blush. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 100:73-81.

Voigt, C. A., Schäfer, W. and Salomon, S. 2005. A secreted lipase of Fusarium graminearum is a virulence factor required for infection of cereals. Plant J. 42:364-375.

Wagacha, J. M. and Muthomi, J. W. 2007. Fusarium culmorum: infection process, mechanisms of mycotoxin production and their role in pathogenesis in wheat. Crop Prot. 26:877-885.

Wallwork, H., Butt, M., Cheong, J. P. E. and Williams, K. J. 2004. Resistance to crown rot in wheat identified through an improved method for screening adult plants. Australas. Plant Pathol. 33:1-7.

Wang, H., Hwang, S. F., Eudes, F., Chang, K. F., Howard, R. J. and Turnbull, G. D. 2006. Trichothecenes and aggressiveness of Fusarium graminearum causing seedling blight and root rot in cereals. Plant Pathol. 55:224-230.

Wang, Q., Vera Buxa, S., Furch, A., Friedt, W. and Gottwald, S. 2015. Insights into Triticum aestivum seedling root rot caused by Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant.-Microbe. Interact. 28:1288-1303.

Wildermuth, G. B., McNamara, R. B. and Quick, J. S. 2001. Crown depth and susceptibility to crown rot in wheat. Euphytica 122:397-405.

Winter, M., Koopmann, B., Döll, K., Karlovsky, P., Kropf, U., Schlüter, K. and von Tiedemann, A. 2013. Mechanisms regulating grain contamination with trichothecenes translocated from the stem base of wheat (Triticum aestivum) infected with Fusarium culmorum. Phytopathology 103:682-689.

Xu, F., Yang, G., Wang, J., Song, Y., Liu, L., Zhao, K., Li, Y. and Han, Z. 2018. Spatial distribution of root and crown rot fungi associated with winter wheat in the North China plain and its relationship with climate variables. Front. Microbiol. 9:1054.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print