|

|

| Plant Pathol J > Volume 38(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Erwinia amylovora, the causal agent of fire-blight disease in apple and pear trees, was first isolated in South Korea in 2015. Although numerous studies, including omics analyses, have been conducted on other strains of E. amylovora, studies on South Korean isolates remain limited. In this study, we conducted a comparative proteomic analysis of the strain TS3128, cultured in three media representing different growth conditions. Proteins related to virulence, type III secretion system, and amylovoran production, were more abundant under minimal conditions than in rich conditions. Additionally, various proteins associated with energy production, carbohydrate metabolism, cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, and ion uptake were identified under minimal conditions. The strain TS3128 expresses these proteins to survive in harsh environments. These findings contribute to understanding the cellular mechanisms driving its adaptations to different environmental conditions and provide proteome profiles as reference for future studies on the virulence and adaptation mechanisms of South Korean strains.

Erwinia amylovora, which belongs to the phylum ╬│-Proteobacteria, is a gram-negative, motile, rod-shaped bacterium with peritrichous flagella (Mansfield et al., 2012). It causes fire blight, one of the most destructive diseases in the family Rosaceae, and poses a global threat to the production of apples and pears in particular (Malnoy et al., 2012). The virulence and biology of E. amylovora strains have been extensively studied worldwide using diverse omics technologies (Mansfield et al., 2012; Piqu├® et al., 2015). However, studies on E. amylovora strains isolated in South Korea remain limited because the fire blight disease was first reported in the country in 2015 (Myung et al., 2016). Thus, in this study, we investigated the cellular mechanisms driving the response of an E. amylovora strain isolated in South Korea to three different sets of conditions via a comparative proteomic analysis.

We used the virulent South Korean E. amylovora strain TS3128, which was isolated from pear trees in Anseong (Myung et al., 2016). The complete genome sequence of this strain was recently reported (Kang et al., 2021). For comparative proteomic analysis, we used a label-free shotgun proteomic technique, following a previously established protocol (Lee et al., 2021). The strain was cultured in three different liquid media: the Luria Bertani medium (LB; 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl in 1 l), an hrp inducing medium (HMM; 1 g of (NH4)2SO4, 0.246 g of MgCl2-6H2O, 0.1 g of NaCl, 8.708 g of K2HPO4, and 6.804 g of KH2PO4 in 1 l), and an amylovoran inducing medium (MBMA; 3 g of KH2PO4, 7 g of K2HPO4, 1 g of (NH4)2SO4, 2 ml of glycerol, 0.5 g of citric acid, and 0.03 g of MgSO4, and 10 g of sorbitol in 1 l). The LB medium was used to simulate rich conditions. The HMM and MBMA media were employed to stimulate minimal conditions as represented by two major factors of E. amylovora virulence: the type III secretion system (T3SS) and amylovoran, respectively (Akhlaghi et al., 2020). Nine bacterial cell samples (three replicates per set of conditions) were taken at an OD600 of 0.15 and disrupted via sonication. Total soluble proteins were collected, concentrated, and digested using trypsin to produce tryptic peptides.

Proteomic analysis was performed at the BT Research Facility Center, Chung-Ang University. One microgram of each sample was analyzed via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The samples were injected into a split-free nano LC setup (EASY-nLC II, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), connected to an LTQ Velos Pro instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the nanospray ion mode. Peptides were identified and quantified using an established protocol (Kim et al., 2021). The mass spectra obtained from LC-MS/MS analysis were analyzed using the Proteome Discoverer software (ver. 1.3.0.399, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and SEQUEST algorithm. Whole proteome data on E. amylovora strain TS3128 (accession no. CP056034 for chromosome and CP056034 for plasmid), obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, was used as the database for this analysis. The target-decoy method was employed to increase the confidence level (Elias and Gygi, 2007). The analyzed data were imported into Scaffold 4 (Proteome Software, Portland, OR, USA) for comparison.

It has been reported that E. amylovora strain TS3128 contains 3,237 and 11 predicted protein-coding sequences (CDSs) in chromosomes and plasmids, respectively (Kang et al., 2021). The number of proteins identified in the nine samples during LC-MS/MS ranged between 1,008 and 1,097, corresponding to approximately 31.03-33.77% of total CDSs (Table 1). The number of proteins shared between the three biological replicates of LB, HMM, and MBMA was 969, 998, and 1,033, respectively. These proteins were used for comparative analysis. The normalized average of peptide spectrum matches (PSMs) in the three biological replicates was calculated (Choi et al., 2008) and quantitatively analyzed to identify proteins with counts significantly different from the mean (over two-fold). A studentŌĆÖs t-test was performed using these PSM values. Proteins with a P-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically different.

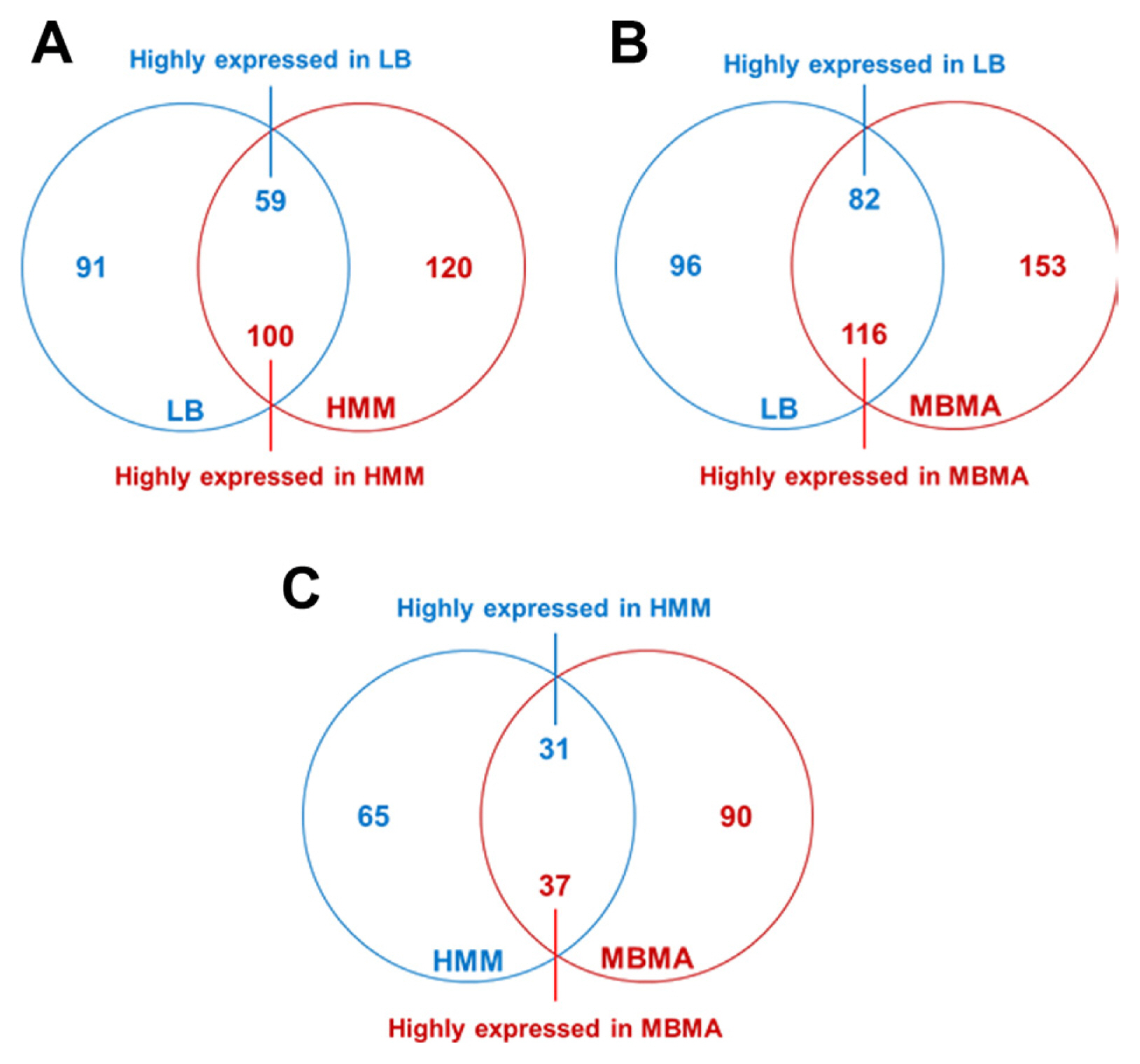

A total of 91 and 120 proteins were unique to LB and HMM, respectively (Fig. 1A). Additionally, 59 and 100 proteins significantly differed in abundance (over two-fold) in LB and HMM, respectively. These results indicate that the expression of approximately 11.4% of the proteins present in strain TS3128 was altered under those conditions. Comparing LB and MBMA, the expression of 447 proteins was altered. Among these, 96 and 153 proteins were unique, and 82 and 116 proteins were significantly abundant (over two-fold) in LB and MBMA, respectively (Fig. 1B). Lastly, 65 and 90 proteins were unique, and 31 and 37 proteins were significantly abundant (over two-fold) in HMM and MBMA, respectively (Fig. 1C). Notably, the number of proteins that significantly differed in abundance between HMM and MBMA (Fig. 1C) was considerably lower than that between LB and HMM and between LB and MBMA (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). This difference is potentially due to the different conditions of the three media. In contrast to LB, a rich medium, both HMM and MBMA represent minimal conditions, unfavorable for bacterial growth.

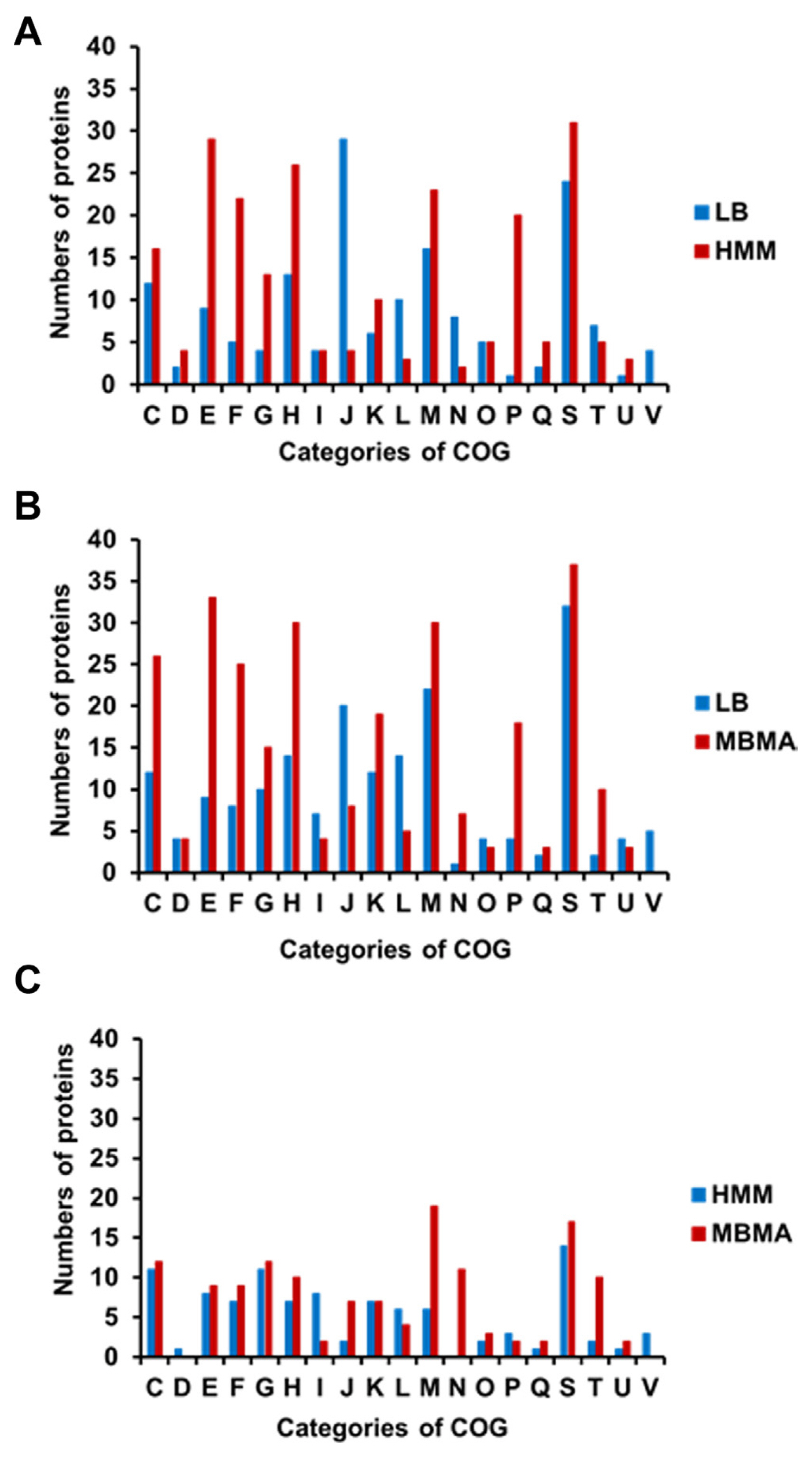

The proteins with significantly different levels of expression were subsequently classified using the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) analysis (Tatusov et al., 2000) to identify the cellular mechanisms driving E. amylovora responses to different conditions. The number of proteins in most categories was higher in HMM than in LB, except for groups J (translation), L (replication/repair), N (transcription), T (signal transduction), and V (defense mechanisms) (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The HMM medium stimulates hrp gene expression in E. amylovora (Lee and Zhao, 2017). Previous studies have shown that the expression of the hairpin protein (HrpN), a T3SS protein secreted by E. amylovora, is stimulated in hrp-inducing minimal media (Gaudriault et al., 1998; Jin et al., 2001). In another study, rich and minimal media respectively suppressed and stimulated hrp gene expression in E. amylovora (Wei et al., 1992). Reflecting these findings, various T3SS proteins were identified using comparative proteomic analysis. The expression of HrpN (QKZ08390), the type III effector protein HrpK (QKZ08359), Hrp pili protein HrpA (QKZ10963), T3SS outer membrane ring subunit SctC (QKZ08387), and T3SS protein (QKZ08595) was also higher in HMM than LB (Supplementary Table 2). This indicates a successful comparative proteomic analysis of LB and HMM.

The HMM medium contained 10 mM galactose. Therefore, we hypothesized that galactose metabolism-related proteins would be abundant in E. amylovora cells cultured in HMM. As expected, the expression of several galactose-related proteins was higher in HMM than that in LB (Supplementary Table 2). This held true for MglB (QKZ09819) and MglA (QKZ09818), which transport galactose, galactokinase (QKZ08930), which produces phosphorylated galactose, and multicopper oxidase CueO (QKZ10250) and peroxiredoxin (QKZ08425), which are related to virulence in gram-negative bacteria (Achard et al., 2010; Kaihami et al., 2014). Notably, the number of proteins in group N (motility) was much higher in LB than that in HMM. The expression of T3SS- and flagellar-related proteins is negatively cross-controlled in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Soscia et al., 2007). Therefore, it is likely that motility-related protein levels were lower in HMM than that in LB because of the high expression of T3SS proteins in HMM. The expression of glycosyl transferase (QKZ09182) and the omptin family outer membrane protease (QKZ11062) was also higher in HMM than that in LB. Glycosyl transferase and bacterial protease are related to virulence and other cellular mechanisms in pathogenic bacteria (Brannon et al., 2015; Li and Wang, 2012). The comparative proteomic analysis of this study reveals that E. amylovora likely secretes higher levels of various proteins associated with virulence in HMM than those in LB.

In addition, 28 proteins related to energy production and conversion were identified in LB and HMM. For example, a formate dehydrogenase accessory sulfurtransferase, FdhD (QKZ07880), was activated in HMM. In a previous study, FdhD was determined to be essential for formate dehydrogenase in Escherichia coli and contribute to oxidative stress tolerance (Iwadate et al., 2017). Moreover, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and hydrogen (NADH)-quinone oxidoreductase subunit L (QKZ09880), subunit NuoH (QKZ09884), and quinone oxidoreductase (QKZ10653) were more abundant in HMM than LB. The NADH-quinone oxidoreductase protein complex is the first in the electron transport chain (Spero et al., 2015). In addition, numerous organic and inorganic ATP-binding cassette transporters were detected in LB and HMM (Supplementary Table 2). Such ATP-binding cassette transporters are important factors of virulence, and their expression is likely stimulated by exposure to harsh environments and host conditions (Zeng and Charkowski, 2021). Therefore, E. amylovora likely expressed proteins related to energy production, stress tolerance, and uptake to survive in the harsh, growth-inhibiting conditions of HMM.

The distribution of proteins observed in the COGs comparison of LB and MBMA was similar to that of LB and HMM (Fig. 2B). The synthetic MBMA medium creates conditions conducive to amylovoran biosynthesis (Lee and Zhao, 2017). As expected, five proteins related to amylovoran biosynthesis (QKZ09777, QKZ09779, QKZ09783, QKZ09861, and QKZ08087) were observed exclusively in MBMA (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). In addition, the transcriptional regulator RcsB (QKZ09861) was more abundant in MBMA than in LB (Supplementary Table 4). In previous studies, RcsB positively regulated amylovoran production and contributed to the virulence of E. amylovora (Ancona et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2009). Proteins in group M (cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis) were less abundant in LB than in MBMA. Among these proteins, two TonB-dependent receptors (QKZ08834 and QKZ09398) were detected exclusively in MBMA. Other studies have shown that the TonB-dependent receptor is important for virulence and utilizing iron substrates (Kachadourian et al., 1996). Some outer membrane-related proteins-OmpA (QKZ07876), OmpC (QKZ10993), and OmpW (QKZ11016)-were expressed more or detected exclusively in MBMA. As shown in a previous study, OmpA and OmpC influence the virulence of Gram-negative bacteria (Vila-Farr├®s et al., 2017) and E. coli (Hejair et al., 2017), respectively. Meanwhile, OmpW has been widely found in Gram-negative bacteria responding to antibiotic stress and environmental stimuli (Xiao et al., 2016). In addition, outer membrane assembly proteins of the AsmA family (QKZ10885, QKZ07930, and QKZ09789) were more abundant in MBMA than in LB. The AmsA protein family is related to membrane biosynthesis and lipopolysaccharide production, a major virulence factor (Deng and Misra, 1996). This likely explains why E. amylovora produced more proteins related to virulence in MBMA than in LB.

In a previous study, sorbitol, a component of MBMA, triggered a high level of amylovoran production in E. amylovora (Bellemann et al., 1994). Sorbitol-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (QKZ10463) can be used by E. amylovora to utilize sorbitol for carbohydrate transport in the host plant and the interconversion of sorbitol to fructose (Salomone-Stagni et al., 2018). Therefore, because the expression of sorbitol-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was higher in MBMA than that in LB, it is likely that sorbitol was used as a carbon source by E. amylovora cells cultured in the former. Additionally, the phosphotransferase transport system (PTS) glucitol/sorbitol transporter subunits IIA (QKZ10464) and IIB (QKZ10465) and glucitol/sorbitol permease IIC (QKZ10466) were expressed more in MBMA than in LB. Many carbohydrates, including sorbitol, are transported into bacterial cells via the PTS (Kotrba et al., 2001). The various proteins related to the transport of sorbitol as a sugar source expressed in MBMA may contribute to the production of amylovoran. Moreover, the universal stress protein UspA (QKZ07979) was more abundant in MBMA than in LB. A previous study reported that UspA is crucial for the virulence of Salmonella (Liu et al., 2007). These results indicate that E. amylovora cultured in MBMA expresses various proteins associated with virulence.

The distribution of categorized proteins in HMM and MBMA differed from that of the other two comparisons (Fig. 2C). The number of proteins expressed in most groups in HMM and MBMA was similar. Notably, more proteins in group I (lipid metabolism) were expressed in HMM than in MBMA. In contrast, the number of proteins in groups J (translation), M (cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis), and N (cell motility) in MBMA was considerably higher than those in HMM (Fig. 2C). Overall, the expression of proteins associated with sorbitol metabolism was higher in MBMA, whereas galactose-related proteins were more abundant in HMM (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). This difference was possibly due to the composition of the media.

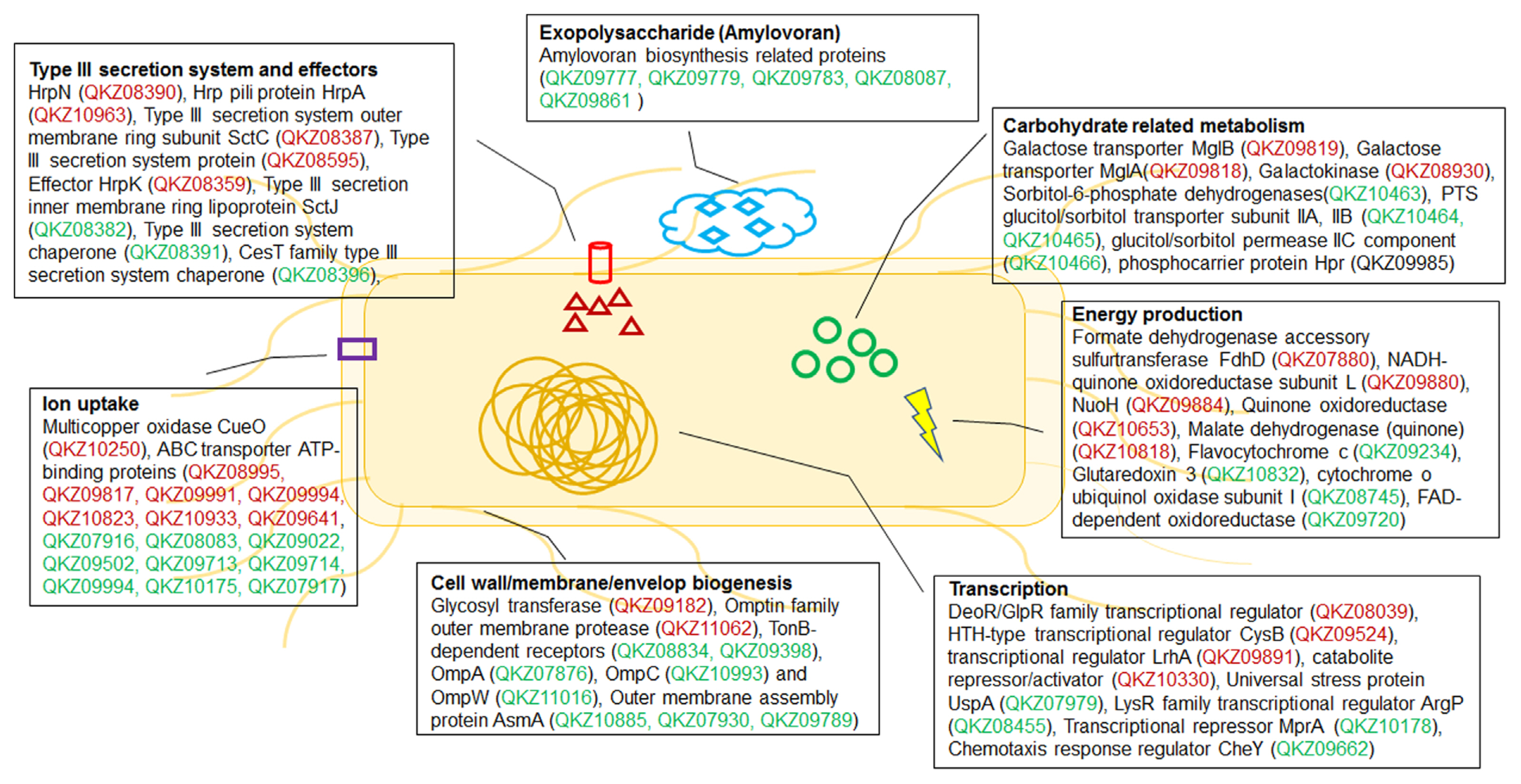

In this study, we used an E. amylovora strain isolated from South Korea to investigate the mechanisms driving the expression of different proteins under three different sets of conditions. Many virulence-related proteins, including those involved in T3SS and amylovoran production, were expressed more under minimal conditions than in rich condition (Fig. 3). In addition, various proteins expressed in the three groups of samples were related to carbohydrate metabolism, energy production, ion uptake, transcription, and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis. These results serve as a valuable point of reference for studying the virulence and adaptation mechanisms of South Korean strains of E. amylovora.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with the support of the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Grant No. PJ014934), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. This research was also supported by the Chung-Ang University Graduate Research Scholarship in 2022 (awarded to Junhyeok Choi).

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at The Plant Pathology Journal website (http://www.ppjonline.org/).

Fig.┬Ā1

Comparative proteomic analyses of Erwinia amylovora cultured in Luria Bertani (LB), hrp inducing (HMM), and amylovoran inducing (MBMA) media. The Venn diagrams display the numbers of proteins that exhibited significant differences in abundance (over two-fold) between the (A) LB and HMM, (B) LB and MBMA, and (C) HMM and MBMA samples.

Fig.┬Ā2

Classification of differentially abundant proteins from the comparative proteomic analysis using clusters of orthologous groups. The bar graphs show numbers of classified proteins from different media (A) Luria Bertani (LB) vs. hrp inducing (HMM), (B) LB vs. amylovora inducing (MBMA), and (C) HMM vs. MBMA. Functional groups: C, energy production and conversion; D, cell cycle control and mitosis; E, amino acid metabolism and transport; F, nucleotide metabolism and transport; G, carbohydrate metabolism and transport; H, coenzyme metabolism; I, lipid metabolism; J, translation; K, transcription; L, replication and repair; M, cell wall/membrane/envelop biogenesis; N, cell motility; O, post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperone functions; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary structure; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction; U, intracellular trafficking and secretion; V, defense mechanisms.

Fig.┬Ā3

Diagram of putative mechanisms driving Erwinia amylovora responses to minimal and rich conditions. Red and green indicate more abundant proteins in hrp inducing (HMM) and amylovoran inducing (MBMA; minimal) and Luria Bertani (LB; rich) media, respectively. The diagram shows selected proteins from the list.

Table┬Ā1

Number of proteins and PSM values of Erwinia amylovora cell samples cultured in LB, HMM, and MBMA media, measured via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

References

Achard, M.E.S., Tree, J.J., Holden, J.A., Simpfendorfer, K.R., Wijburg, O.L.C., Strugnell, R.A., Schembri, M.A., Sweet, M.J., Jennings, M.P. and McEwan, A.G. 2010. The multi-copper-ion oxidase CueO of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is required for systemic virulence. Infect. Immun 78:2312-2319.

Akhlaghi, M., Tarighi, S. and Taheri, P. 2020. Effects of plant essential oils on growth and virulence factors of Erwinia amylovora

. J. Plant Pathol 102:409-419.

Ancona, V., Chatnaparat, T. and Zhao, Y. 2015. Conserved aspartate and lysine residues of RcsB are required for amylovoran biosynthesis, virulence, and DNA binding in Erwinia amylovora

. Mol. Genet. Genomics 290:1265-1276.

Bellemann, P., Bereswill, S., Berger, S. and Geider, K. 1994. Visualization of capsule formation by Erwinia amylovora and assays to determine amylovoran synthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 16:290-296.

Brannon, J.R., Burk, D.L., Leclerc, J.-M., Thomassin, J.-L., Portt, A., Berghuis, A.M., Gruenheid, S. and Le Moual, H. 2015. Inhibition of outer membrane proteases of the omptin family by aprotinin. Infect. Immun 83:2300-2311.

Choi, H., Fermin, D. and Nesvizhskii, A.I. 2008. Significance analysis of spectral count data in label-free shotgun proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7:2373-2385.

Deng, M. and Misra, R. 1996. Examination of AsmA and its effect on the assembly of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins. Mol. Microbiol 21:605-612.

Elias, J.E. and Gygi, S.P. 2007. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4:207-214.

Gaudriault, S., Brisset, M.-N. and Barny, M.-A. 1998. HrpW of Erwinia amylovora, a new Hrp-secreted protein. FEBS Lett 428:224-228.

Hejair, H.M.A., Zhu, Y., Ma, J., Zhang, Y., Pan, Z., Zhang, W. and Yao, H. 2017. Functional role of ompF and ompC porins in pathogenesis of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli

. Microb. Pathog 107:29-37.

Iwadate, Y., Funabasama, N. and Kato, J.-I. 2017. Involvement of formate dehydrogenases in stationary phase oxidative stress tolerance in Escherichia coli

. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 364:fnx193.

Jin, Q., Hu, W., Brown, I., McGhee, G., Hart, P., Jones, A.L. and He, S.Y. 2001. Visualization of secreted Hrp and Avr proteins along the Hrp pilus during type III secretion in Erwinia amylovora and Pseudomonas syringae

. Mol. Microbiol 40:1129-1139.

Kachadourian, R., Dellagi, A., Laurent, J., Bricard, L., Kunesch, G. and Expert, D. 1996. Desferrioxamine-dependent iron transport in Erwinia amylovora CFBP1430: cloning of the gene encoding the ferrioxamine receptor FoxR. Biometals 9:143-150.

Kaihami, G.H., de Almeida, J.R.F., dos Santos, S.S., Netto, L.E.S., de Almeida, S.R. and Baldini, R.L. 2014. Involvement of a 1-Cys peroxiredoxin in bacterial virulence. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004442.

Kang, I.-J., Park, D.H., Lee, Y.-K., Han, S.-W., Kwak, Y.-S. and Oh, C.-S. 2021. Complete genome sequence of Erwinia amylovora strain TS3128, a Korean strain isolated in an asian pear orchard in 2015. Microbiol. Resour. Announc 10:e00694-21.

Kim, M., Lee, J., Heo, L., Lee, S.J. and Han, S.-W. 2021. Proteomic and phenotypic analyses of a putative glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase required for virulence in Acidovorax citrulli

. Plant Pathol. J 37:36-46.

Kotrba, P., Inui, M. and Yukawa, H. 2001. Bacterial phosphotransferase system (PTS) in carbohydrate uptake and control of carbon metabolism. J. Biosci. Bioeng 92:502-517.

Lee, J., Heo, L. and Han, S.-W. 2021. Comparative proteomic analysis for a putative pyridoxal phosphate-dependent aminotransferase required for virulence in Acidovorax citrulli

. Plant. Pathol. J 37:673-680.

Lee, J.H. and Zhao, Y. 2017. ClpXP-dependent RpoS degradation enables full activation of type III secretion system, amylovoran production, and motility in Erwinia amylovora

. Phytopathology 107:1346-1352.

Li, J. and Wang, N. 2012. The gpsX gene encoding a glycosyltransferase is important for polysaccharide production and required for full virulence in Xanthomonas citri subspcitri

. BMC Microbiol 12:31.

Liu, W.-T., Karavolos, M.H., Bulmer, D.M., Allaoui, A., Hormaeche, R.D.C.E., Lee, J.J. and Khan, C.M.A. 2007. Role of the universal stress protein UspA of Salmonella in growth arrest, stress and virulence. Microb. Pathog 42:2-10.

Malnoy, M., Martens, S., Norelli, J.L., Barny, M.-A., Sundin, G.W., Smits, T.H.M. and Duffy, B. 2012. Fire blight: applied genomic insights of the pathogen and host. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 50:475-494.

Mansfield, J., Genin, S., Magori, S., Citovsky, V., Sriariyanum, M., Ronald, P., Dow, M., Verdier, V., Beer, S.V., Machado, M.A., Toth, I., Salmond, G. and Foster, G.D. 2012. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol 13:614-629.

Myung, I.-S., Lee, J.-Y., Yun, M.-J., Lee, Y.-H., Lee, Y.-K., Park, D.-H. and Oh, C.-S. 2016. Fire blight of apple, caused by Erwinia amylovora, a new disease in Korea. Plant Dis 100:1774.

Piqu├®, N., Mi├▒ana-Galbis, D., Merino, S. and Tom├Īs, J.M. 2015. Virulence factors of Erwinia amylovora: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci 16:12836-12854.

Salomone-Stagni, M., Bartho, J.D., Kalita, E., Rejzek, M., Field, R.A., Bellini, D., Walsh, M.A. and Benini, S. 2018. Structural and functional analysis of Erwinia amylovora SrlD: the first crystal structure of a sorbitol-6-phosphate 2-dehydrogenase. J. Struct. Biol 203:109-119.

Soscia, C., Hachani, A., Bernadac, A., Filloux, A. and Bleves, S. 2007. Cross talk between type III secretion and flagellar assembly systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

. J. Bacteriol 189:3124-3132.

Spero, M.A., Aylward, F.O., Currie, C.R. and Donohue, T.J. 2015. Phylogenomic analysis and predicted physiological role of the proton-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (complex I) across bacteria. mBio 6:e00389-15.

Tatusov, R.L., Galperin, M.Y., Natale, D.A. and Koonin, E.V. 2000. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res 28:33-36.

Vila-Farr├®s, X., Parra-Mill├Īn, R., S├Īnchez-Encinales, V., Varese, M., Ayerbe-Algaba, R., Bay├│, N., Guardiola, S., Pach├│n-Ib├Ī├▒ez, M.E., Kotev, M., Garc├Ła, J., Teixid├│, M., Vila, J., Pach├│n, J., Giralt, E. and Smani, Y. 2017. Combating virulence of Gram-negative bacilli by OmpA inhibition. Sci. Rep 7:14683.

Wang, D., Korban, S.S. and Zhao, Y. 2009. The Rcs phosphorelay system is essential for pathogenicity in Erwinia amylovora

. Mol. Plant Pathol 10:277-290.

Wei, Z.M., Sneath, B.J. and Beer, S.V. 1992. Expression of Erwinia amylovora hrp genes in response to environmental stimuli. J. Bacteriol 174:1875-1882.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- ORCID iDs

-

Sang-Wook Han

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0893-1438 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement1

Supplement1 Print

Print