Comparative Genome Analysis of Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953 with Rathayibacter toxicus Strains Can Facilitate Studies on Mechanisms of Nematode Association and Host Infection

Article information

Abstract

Rathayibacter tritici, which is a Gram positive, plant pathogenic, non-motile, and rod-shaped bacterium, causes spike blight in wheat and barley. For successful pathogenesis, R. tritici is associated with Anguina tritici, a nematode, which produces seed galls (ear cockles) in certain plant varieties and facilitates spread of infection. Despite significant efforts, little research is available on the mechanism of disease or bacteria-nematode association of this bacterium due to lack of genomic information. Here, we report the first complete genome sequence of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 with diverse features of this strain. The whole genome consists of one circular chromosome of 3,354,681 bp with a GC content of 69.48%. A total of 2,979 genes were predicted, comprising 2,866 protein coding genes and 49 RNA genes. The comparative genomic analyses between R. tritici NCPPB 1953 and R. toxicus strains identified 1,052 specific genes in R. tritici NCPPB 1953. Using the BlastKOALA database, we revealed that the flexible genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 is highly enriched in ‘Environmental Information Processing’ system and metabolic processes for diverse substrates. Furthermore, many specific genes of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 are distributed in substrate-binding proteins for extracellular signals including saccharides, lipids, phosphates, amino acids and metallic cations. These data provides clues on rapid and stable colonization of R. tritici for disease mechanism and nematode association.

Introduction

As a Gram positive plant pathogen, the genus Rathayibacter is a member of coryneform bacteria belonging to the family Microbacteriaceae of phylum Actinobacteria, previously attributed to genus Clavibacter (Davis et al., 1984). Many coryneform phytopathogenic bacteria were initially classified as the genus Corynebacterium (Dowson, 1942), while many properties of the coryneform plant pathogenic bacteria were different from those of Corynebacterium sensu stricto (Evtushenko and Dorofeeva, 2012). Later, plant pathogenic Corynebacterium species were reclassified into the genus Clavibacter due to the presence of DAB, which is a particular component in peptidoglycan cell wall group B (Carlson and Vidaver, 1982; Davis et al., 1984). In 1993, Zgurskaya and colleagues proposed the genus Rathayibacter such as R. tritici, R. rathayi, and R. iranicus separating from the genus Clavibacter based on DNA-DNA hybridization, chemotaxonomic studies, and numerical analysis of bacterial phenotypes (Evtushenko and Dorofeeva, 2012; Zgurskaya et al., 1993). Separation of Rathayibacter species from Clavibacter was further supported by the analyses of 16S rRNA gene sequences (Rainey et al., 1994; Takeuchi and Yokota, 1994). The species Rathayibacter toxicus was also classified in this genus by Sasaki and colleagues in 1998 (Sasaki et al., 1998). Furthermore, these species of Rathayibacter have been shown to differ absolutely in many physiological phenotypes, including cell-wall compositions, multilocus enzyme profiles, and pigmentations (Davis et al., 1984; De Bruyne et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1997; Riley et al., 1988; Zgurskaya et al., 1993).

R. tritici has been identified as a causative agent of spike blight, also called yellow ear rot, yellow slime rot, or Tundu disease, in wheat and barley (Paruthi and Gupta, 1987). Plant diseases caused by R. tritici result in economic losses in many countries worldwide, including Australia (Riley and Reardon, 1995), China, Cyprus, Iran (Bradbury, 1986; Duveiller and Fucikovsky, 1997; Mehta, 2014) and Pakistan (Akhtar, 1987). Interestingly, R. tritici shows an association with Anguina tritici, a nematode, which produces seed galls (ear cockles) in certain plant varieties and facilitates spread of R. tritici infection (Paruthi and Bhatti, 1985). Intact seed galls produced by nematodes display the greatest grain loss due to development of R. tritici (Fattah, 1988). Similarly, a bacterium, R. toxicus, causing a gumming disease and ryegrass toxicity is associated with a nematode vector (Riley and Ophel, 1992). Compared to R. tritici, R. toxicus is commonly found in annual ryegrass with A. funesta as a nematode vector, rabbit-foot grass and annual browngrass with undescribed Anguina species. While host plants for R. toxicus are limited to ryegrasses in nature, it is likely that R. toxicus is not host specific experimentally (Agarkova et al., 2006). In addition to unique host plants for R. toxicus, R. toxicus is different from R. tritici for the production of glycolipid toxins, known as corynetoxins, in the infected ryegrass, and thus causes a lethal toxicosis in the animal that consumed the infected plants (Agarkova et al., 2006; Jago and Culvenor, 1987). Both in R. tritici and R. toxicus, bacterial association with a nematode vector could be used as a good model of interaction between plant pathogens and nematodes for successful pathogenesis. Despite significant efforts and interesting association between bacterial pathogen and nematodes, little research is available on the mechanism of disease or bacteria-nematode association of this bacterium due to lack of genomic information.

Characterising the complete genome of R. tritici could help to resolve these gaps in our understanding. Here, we report the first whole genome sequence of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 isolated from wheat seeds. The whole genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 harbours one circular chromosome of 3,354,681 bp with 2,866 protein coding genes. The comparative genomic analysis between R. tritici NCPPB 1953 and R. toxicus strains showed a lot of 1,052 R. tritici NCPPB 1953-specific genes in flexible genome, which refers to genes present in two or more organisms or specific to a single organism in a pan-genome (Medini et al., 2005; Sternes and Borneman, 2016). We revealed that these genes are responsible for ‘Environmental Information Processing’ system and metabolic processes for diverse substrates, which might explain the rapid and stable growth of R. tritici rather than R. toxicus. Furthermore, distinctive genetic features of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 are distributed in substrate-binding proteins for extracellular signals. More research is required to better understand the pathogenesis of R. tritici and association with the nematode, and complete genomic information of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 will provide a valuable foundation for diverse biological experiments.

Materials and Methods

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

Pure culture of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was grown on nutrient broth yeast extract (NBY) media (8 g nutrient broth, 2 g yeast extract, 2 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 2.5 g glucose per liter, followed by autoclaving and supplementation with 1 ml of 1 M MgSO4·7H2O) media for 96 h at 25°C (Zgurskaya et al., 1993). For extraction of genomic DNA, the pellet of bacterial cells grown on the agar plate was harvested with sterilized water. DNA was subsequently isolated using the Promega Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer. DNA was visualized in ethidium bromide-stained 0.7% agarose gel, and the concentration and purity of DNA were determined by a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer.

Genome sequencing of R. tritici NCPPB 1953

Third generation DNA sequencing of the SMRT technology (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) was used to establish the complete genome sequence of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 (Chin et al., 2013). A total of 150,292 raw reads containing an average of 7,236 bp were generated by a 20-kb insert SMRTbell standard library. To correct errors, long reads were selected as seeds, and other short reads were aligned into seeds by the basic local alignment with successive refinement step (Chaisson and Tesler, 2012). After filtration, post-filtered reads included 86,775 reads and represented an average of 11,144 bp with a quality of 0.852. The de novo assembly of post-filtered reads was conducted using the HGAP pipeline from SMRT-Analysis with default parameters (Chin et al., 2013). Circularization was verified, and overlapping ends were trimmed (Kopf et al., 2014). Assembly resulted in a single contig with a circular form of 3,354,681 bp. Subsequently, to evaluate assembly quality, all reads were mapped back to the chromosomal sequence according to the RS_Resequencing protocol. Final results indicate bases called value of 99.88%, consensus concordance of 100%, and 187.88-fold coverage.

Gene annotation of R. tritici NCPPB 1953

Genomic rRNAs and tRNAs were predicted using RNAmmer (Lagesen et al., 2007) and tRNAscan-SE (Lowe and Eddy, 1997), respectively. All open reading frames (ORFs) and pseudogenes were predicted using Glimmer (Delcher et al., 1999), GeneMarkHMM (Lukashin and Borodovsky, 1998) and Prodigal (Hyatt et al., 2010). Predicted ORFs with nucleotides were translated into amino acid sequences and then searched using the BLAST algorithm (Altschul et al., 1990) against the NCBI-NR (Benson et al., 2000), Pfam (Finn et al., 2016) and UniProt (UniProt Consortium, 2013) databases for a description of each protein. In addition, the KEGG (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) and COG (Galperin et al., 2015) databases were used to construct functional categories in accordance with biological systems. Genes in internal clusters were detected using BLASTclust (Alva et al., 2016) with significant cutoffs of 70% coverage and 30% identity. Signal peptides and transmembrane helices were based on SignalP (Petersen et al., 2011) and TMHMM (Krogh et al., 2001), respectively. CRISPRFinder was used to identify the CRISPR (Grissa et al., 2007). Predicted genes were compared with the Pathogen-Host Interaction (PHI) database (Urban et al., 2015) using the BLASTp method and an e-value cutoff of 1.0 × 10−5 (Buiate et al., 2017). The annotation results were verified using the Artemis (Rutherford et al., 2000).

Nucleotide sequence accession number of R. tritici NCPPB 1953

The complete genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 has been deposited in GenBank (Benson et al., 2000) under accession number CP015515.

Phylogenetic analysis

To evaluate evolutionary distances among R. tritici NCPPB 1953 and closely related bacteria in the genus Rathayibacter, we collected all 16S rRNA sequences of 26 bacteria from the SILVA database. The ClustalW tool was used to align all sequences with default parameters (Larkin et al., 2007). Phylogenetic tree was conducted by the Maximum Likelihood algorithm based on the Tamura-Nei model as implemented in MEGA 7.0 tool (Kumar et al., 2016). The corresponding parameter of the Maximum Likelihood algorithm was set as ‘complete deletion’. The evolutionary test was performed by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications.

Comparative genome analysis

For this analyses, three complete genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 (accession no. CP015515), R. toxicus WAC3373 (accession no. CP013292), and R. toxicus 70137 (accession no. CP010848) were obtained from GenBank (Benson et al., 2000). We employed the Mauve tool to compare whole genome sequences (Darling et al., 2004). The progressive Mauve algorithm was used to identify genomic rearrangements among whole genome sequences. The alignment was performed using default parameters.

Pan-genome analysis

Genomic information of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was formatted for a reference database using the formatdb tool of BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990). The local BLASTp compared total protein genes of R. toxicus WAC3373 and R. toxicus 70137 to reference database of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 through amino acid sequences. The BLAST outputs were filtered with significant criteria of 50% coverage, 50% identity, and an e-value cutoff of 1.0 × 10−5 to exclude random hits (Anderson and Brass, 1998). By sorting e-value, the best matched subject was selected from total results per each query. Subsequently, to investigate biological meaning of R. tritici NCPPB 1953-specific genes, we used the BlastKOALA tool as an automatic annotation server for genome and metagenome sequences (Kanehisa et al., 2016). The BlastKOALA performed KEGG orthology assignments to characterize individual gene functions and reconstruction of KEGG pathways and modules in R. tritici NCPPB 1953. Also, we constructed networks of some genes related to transport system using the Cytoscape tool (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

Results and Discussion

General features of R. tritici NCPPB 1953

R. tritici NCPPB 1953 is a Gram positive, non-motile, and rodshaped bacterium. Its size is 1.1–1.6 μm long and 0.5–0.6 μm wide (Fig. 1). On an aerobic NBY agar plate, R. tritici NCPPB 1953 formed round colonies and produced yellow pigment within 96 h at 25°C (Fig. 1D) and could grow in a pH range of 6–8. This strain was a non-motile bacterium and cells of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 were short, straight or slightly curved rods with blunt ends. Cells occurred singly, in pairs or sometimes in aggregates (Fig. 1A, B). This is likely because divided cells by binary fission failed to separate after septum formation. Cells were surrounded by a capsule and the capsular material sometimes exhibited distinct extracellular outer layers (Fig. 1C; black arrows). Bacterial colonies were often variable in size, probably because of capsules and bacterial cell aggregates.

Image of transmission electron microscope (TEM) photomicrograph (A–C) and the appearance of colony morphology on solid media (D) of Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953. Cells were grown in NBY agar plate for 96 h. The magnification rates of TEM for A–C were 15,000×, 25,000×, and 10,000×, respectively. Bacterial capsules with extracellular outer layer were observed (black arrows).

Phylogenetic analysis of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 with closely-related bacteria species

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the 16S rRNA genes of 26 different bacteria in the genus Rathayibacter: 3 strains, R. caricis; 3 strains, R. festucae; 3 strains, R. iranicus; 3 strains, R. rathayi; 5 strains, R. toxicus; 9 strains, R. tritici (Fig. 2). All 16S rRNA sequences were downloaded from the SILVA (Quast et al., 2013), providing information on small (16S/18S, SSU) and large (23S/28S, LSU) subunit ribosomal RNA databases. Pairwise distances were estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood approach (Supplementary Table 1). All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 994 positions in the final dataset. As a result, R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was grouped with most of R. tritici strains. R. tritici ATCC 11402 and R. tritici DSM 7486T represented the closest bacteria as both distance value 0.000, followed by R. rathayi DSM 7485T (distance value 0.001), R. tritici ICPB70004 (distance value 0.001), and R. iranicus DSM 7484T (distance value 0.003) (Supplementary Table 1).

16S rRNA phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953 (shown in bold print) with other members in the genus Rathayibacter. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW and the phylogeny was inferred from the alignment of 1,267 bp of 16S rRNA using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model with MEGA 7.0 software. The bootstrap consensus tree from 1,000 replicates was performed to assess the support of the clusters. The scale bar indicates 0.01 nucleotide change per nucleotide position. The GenBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses.

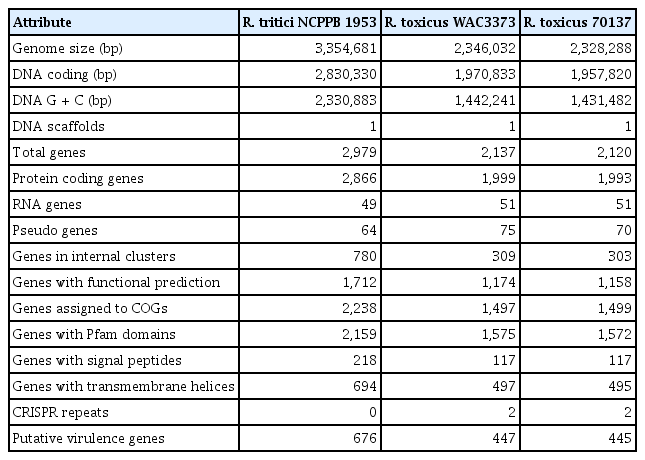

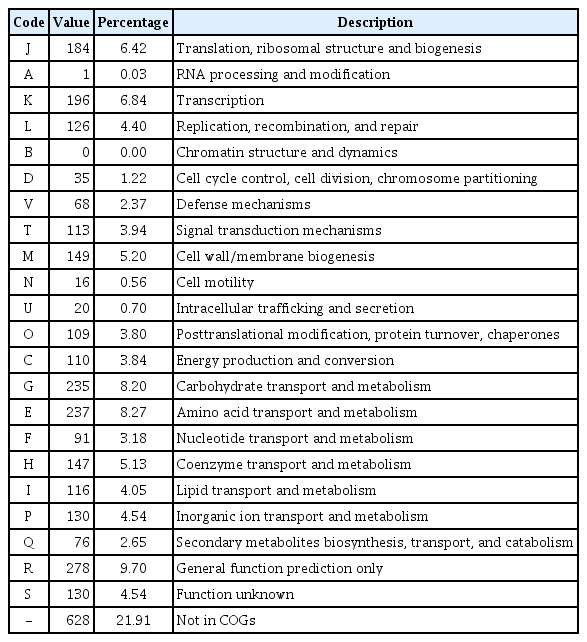

General genomic features of R. tritici NCPPB 1953

The complete genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 consists of a single circular form of 3,354,681 bp with 69.48% GC content. There are 2 rRNA operons, 43 tRNAs, and 64 pseudogenes (Table 1). The chromosome contains 2,866 protein-coding genes. Of these, 1,712 proteins are assigned to functional annotations, whereas 1,154 proteins are considered as hypothetical proteins. Table 2 shows the number of genes associated with general COG functional categories. The ‘General function prediction only’ (9.70%) represents the largest category, followed by ‘Amino acid transport and metabolism’ (8.27%), ‘Carbohydrate transport and metabolism’ (8.20%), ‘Transcription’ (6.84%), and ‘Translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis’ (6.42%). A complete genomic map of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was constructed using the CGView tool in Fig. 3.

Graphical circular map of Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953 chromosome displaying relevant genetic features. From centre to outside: 1, positive (green) and negative (yellow) of GC skew; 2, GC content (black); 3, CDSs on reverse strand (blue); 4, CDSs on forward strand (red); 5, pseudogenes (grey); 6, tRNAs (brown); 7, rRNAs (pink). This figure was built using the CGView tool.

So far, it is hard to find virulence factors of R. tritici NCPPB 1953, since there is a lack of research on the pathogenesis and virulence mechanisms of R. tritici. We therefore performed detection of putative virulence genes in the R. tritici NCPPB 1953 genome using the PHI database that archives the list of experimentally verified pathogenicity, virulence, and effectors from diverse microbes (Urban et al., 2015). A total of 676 putative virulence genes were identified by the significant cutoff of 1.0 × 10−5 e-value (Table 1). R. tritici NCPPB 1953 had about 200 more virulence genes than R. toxicus strains (447 virulence genes in WAC3373 and 445 virulence genes in 70137). Detailed information with putative virulence genes of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was listed in Supplementary Table 2. Most of putative virulence genes in R. tritici NCPPB 1953 were distributed in many plant pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Magnaporthe oryzae, which causes a serious disease affecting rice (Wilson and Talbot, 2009), represented the largest category matched with 58 genes of R. tritici NCPPB 1953, followed by Xanthomonas citri (matched with 36 genes), Fusarium graminearum (matched with 32 genes), and Pseudomonas cichorii (matched with 21 genes). In particular, the X. citri mutant of the gene pstB (encoding the ABC phosphate transporter subunit), which are matched with 30 genes of R. tritici NCPPB 1953, revealed a complete absence of symptoms (Moreira et al., 2015). It was also reported that the gene ABC4 (matched with 16 genes of R. tritici NCPPB 1953) of ABC superfamily of membrane transporters is required for the pathogenicity of M. oryzae, helping the fungus to cope with the cytotoxic environment within host (Gupta and Chattoo, 2008). This data suggests that many virulence genes in R. tritici NCPPB 1953 are implicated to play a role in the membrane transporters to control efflux and influx of host metabolites for their pathogenicity.

The comparative genomic analysis between R. tritici NCPPB 1953 and R. toxicus strains

R. toxicus shares major biological properties compared to R. tritici. For examples, a gumming disease was reported as a common plant disease caused by both R. tritici and R. toxicus (Agarkova et al., 2006; Arif et al., 2016). Also, R. toxicus uses several species of Anguina as the vector system to carry themselves into the plant host like R. tritici (Price et al., 1979; Riley, 1992). Riley and Reardon (1995) discussed the potential of R. tritici as a biological control for R. toxicus because of co-occurrence of two bacteria. Thus, R. toxicus is the important source for comparative analysis with R. tritici and we intended to find distinctive genetic features of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 through comparative genomic analysis between R. tritici and R. toxicus. Among R. toxicus strains, there are two complete genomes in the GenBank (Benson et al., 2000) including R. toxicus WAC3373 and R. toxicus 70137 under accession number CP013292 and CP010848, respectively. Based on the pairwise BLAST comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequences, R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was closely related to R. toxicus, resulting in 100% coverage and 98% identity in both comparisons with R. toxicus WAC3373 and R. toxicus 70137. A similar distribution of rRNA and tRNA genes was maintained as follows: 6 rRNAs and 43 tRNAs, R. tritici NCPPB 1953; 6 rRNAs and 45 tRNAs, R. toxicus WAC3373; 6 rRNAs and 45 tRNAs, R. toxicus 70137.

However, there are different features between R. tritici and R. toxicus in the genome-wide level. GC contents of whole genome sequence showed a large discrepancy between R. tritici (GC content 69.5%) and R. toxicus (GC contents 61.5% in WAC3373 and 61.5% in 70137). Above all, R. tritici NCPPB 1953 harbours a larger genomic size (about 3.35 Mbp) and more genes (2,979 genes), when compared to R. toxicus WAC3373 (about 2.35 Mbp and 2,137 genes) and R. toxicus 70137 (about 2.33 Mbp and 2,120 genes). Indeed, we revealed the dynamic genomic rearrangement of whole genome sequence between R. tritici and R. toxicus using the Mauve aligner (Darling et al., 2004). In Fig. 4, R. tritici NCPPB 1953 shared a total of 58 locally collinear blocks (LCBs), which are highly homologous regions among genome sequences, in comparison to R. toxicus. Although these LCBs covered most parts of the whole genome in R. tritici NCPPB 1953, most of LCBs showed sporadic inversion and irregular genomic rearrangement caused by local and/or large-scale changes in genetic loci. In addition to the variable rearrangement, we confirmed additional genetic differences in R. tritici NCPPB 1953 such as non-matched regions and some LCBs of low similarities. Medini et al. (2005) reported that conserved core regions of microbial genome are responsible for basic aspects of the biology related to essential phenotypes and growth, whereas each flexible genome allows bacteria to obtain supplementary biochemical functions as selective advantages. Consequently, this data suggests that R. tritici NCPPB 1953 have needed additional genetic elements and functions, which could provide effective physiological activity in accordance with specific environment and conditions.

Whole genome alignment of Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953, Rathayibacter toxicus WAC3373, and Rathayibacter toxicus 70137. The top, middle, and bottom sequences represent each genomic sequence of R. tritici NCPPB 1953, R. toxicus WAC3373, and R. toxicus 70137, respectively. Identically coloured boxes by same lines are locally collinear blocks, indicating homologous and conservative regions in both genomes. Coloured bars inside boxes are related to the level of sequence similarities. Numbers above the map show nucleotide positions.

Functional analyses of flexible genome in R. tritici NCPPB 1953 compared to R. toxicus strains

To investigate the biological meaning of distinctive genetic elements in R. tritici NCPPB 1953, we performed the pangenome analysis of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 compared to R. toxicus WAC3373 and R. toxicus 70137, leading to identification of 1,052 R. tritici NCPPB 1953-specific genes (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, 1,052 genes were identified through the BlastKOALA algorithm to infer high-level functions of gene clusters (Kanehisa et al., 2016). As a result, the highest enriched system was ‘Environmental Information Processing’ (72 genes) related to sensing signals and responses to diverse stimuli (Fig. 5). Also, many metabolic processes for substrates were observed in enriched systems as follows: ‘Carbohydrate metabolism’, 28 genes; ‘Amino acid metabolism’, 21 genes; ‘Nucleotide metabolism’, 15 genes; ‘Metabolism of cofactors and vitamins’, 14 genes; ‘Energy metabolism’, 12 genes (Fig. 5). These results indicate that flexible genome in R. tritici NCPPB 1953 have been mainly developed to sense and process diverse substrates from the environment.

Summary of biological systems in Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953-specific genes. A distribution of the KEGG systems is displayed as a pie-chart. The number of gene counts is shown inside each pie of categories. Total 11 KEGG terms are displayed.

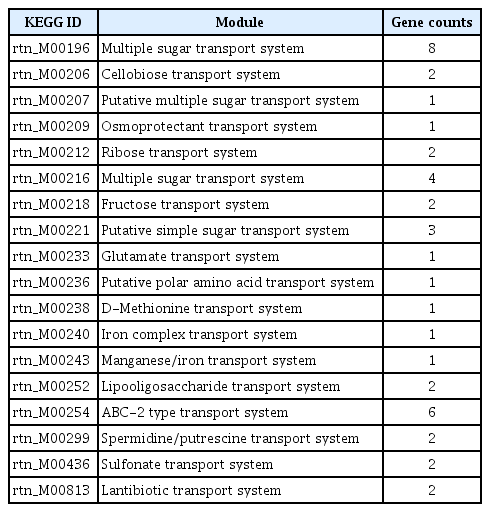

In general, the environment with host condition is far away from the optimal growth conditions for bacteria than experimental conditions with rich media due to multiple stresses (Shimizu, 2013; Yadeta and Thomma, 2013). The acquisition of nutrients of plant pathogens in hostile environment is a fundamental challenge against an extremely low level of organic and inorganic compounds (Yadeta and Thomma, 2013). Pathogens have to need the ability to sense, process, and respond to a variety of substrates and stresses for survival (Shimizu, 2013). Until now, diverse mechanisms for sensing and processing exogenous metabolites within host have been intensively studied in many pathogens (Divon et al., 2006; Jones and Wildermuth, 2011; Wooldridge and Williams, 1993). Our module enrichments showed that most genes in the ‘Environmental Information Processing’ system are associated with recognition and transport of many substrates, including saccharides, lipids, phosphates, amino acids, metallic cations, minerals, organic ions, and vitamins (Table 3). Flexible genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953 was particularly distributed in substrate-binding proteins of transport system (Fig. 6), which is a key determinant of the extracellular signals and high affinity of uptake systems (Maqbool et al., 2015). In this regard, there are interesting reports on the flexible growth and colonization of R. tritici than R. toxicus (Bradbury, 1973; Riley and Ophel, 1992). In 1992, Riley and Ophel reported that R. tritici grows more rapidly than R. toxicus in culture (Riley and Ophel, 1992). It was reported that R. tritici successfully colonizes in plant hosts such as the gummosis of seed heads rather than R. toxicus (Bradbury, 1973). Therefore, we suggests that distinctive genetic features in flexible genome help R. tritici NCPPB 1953 to establish the stable growth and colonization in diverse environments through effective recognition of substrates. Further studies could lead to a better understanding of interactions between R. tritici and nematode as well as R. tritici and plant hosts.

Modules related to ‘Environmental Information Processing’ in Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953-specific genes

The network of Rathayibacter tritici NCPPB 1953 in KEGG transporter. Pathway maps of KEGG transporter system were constructed by the Cytoscape tool. The KEGG database was used to download the data source. There are two color types in the rectangle node: red, genes belonging to flexible genome of R. tritici NCPPB 1953; green, genes belonging to the core genome among R. tritici NCPPB 1953, R. toxicus WAC3373, and R. toxicus 70137.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Research of Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, South Korea and with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Development (PJ01110502)”, Rural Development Administration, South Korea.